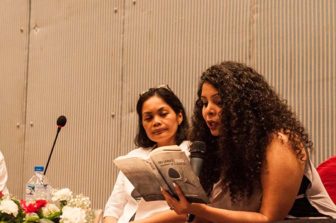

Rana Ayyub speaking at Uncovering Asia 2016 in Nepal. Photo by Sashi Shrestha.

Indian journalist Rana Ayyub has herself become major news since the release of Gujarat Files, which she self-published in May. The book chronicles an eight-month sting operation, in which Ayyub went undercover as an American film student in India to find out what really happened during the 2002 riots in Gujarat, which resulted in thousands dead and injured. The investigation implicated India’s top officials, including current prime minister Narenda Modi, and has been met with a media blackout.

Ayyub’s journalistic success has come at a great personal price, she told journalist Surbhi Kaul during the Uncovering Asia 2016 conference in Kathmandu, Nepal. Following is a lightly edited interview transcript.

What was the biggest reason you pursued this story?

These are things I have been hearing in off-the-record conversations with various people over the years from the time of the Gujarat riots till now. These people [I recorded] only added to what I knew. Even before Gujarat Files was released I knew it would be a big success … The biggest driving factor was that I had the truth by my side, I had the facts by my side and most importantly, I had the tapes with me. The fact that it was censored so badly made me want to do this story, as I wanted to prove a point that high profile people sitting in media houses cannot decide which media story can or cannot go out. I believed in the story, I believed every bit of it.

What have been some of the impacts on your personal life?

Rana Ayyub speaking at Uncovering Asia 2016 in Nepal. Photo by Sashi Shrestha.

I remember my parents got a marriage proposal for me before the book was launched and they [the boy’s family] said, “Damn, your daughter is really controversial, she is so popular, our son really shouldn’t get married to her because he is a pretty ordinary guy who lives a great life and we don’t want him to get into any controversies.” In a way that was a boon for me because I knew what I was saved from.

Having said that, I have been addicted to sleeping pills, I have got an anxiety disorder, I go to a psychiatrist, I go for meditation. Plus, there has also been a great deal of disappointment with this investigation. When a journalist comes and tells me ‘I want to do a sting operation,’ the first thing I tell them is not to go ahead until your organisation backs you. Because I know that many undercover operations in India have not seen the light of the day. It made me cynical to an extent, but I think Gujarat Files has made me a better person. Barring the sleeping issues, anxiety and panic attacks in flights, I think it has been a big blessing for me.

As a woman journalist, was it easier for you to gain the trust of the people you covered in the sting operation?

No, I think it was tougher for me. I have never really seen myself as a woman journalist, I see myself only as a journalist. But I think it becomes a lot tougher for you because you are not taken seriously. They don’t even take you seriously enough to have an off-the-record conversation. In my undercover investigation, I had to make sure that I looked the least attractive, so I wore a bandana and tried to be professional throughout, trying very carefully to not give out any signal which could make them think of me like an object. I did not let them objectify me. I think my strength was being a journalist backed by facts, and that’s all that came to my rescue.

When you assumed the persona of Maithili Tyagi you were all of 26, what do you think you should have known at that time?

I should have been a little less emotional about my story and ready to accept that the story can be rejected and not take it to heart.

You have met various journalists from different nations in Kathmandu. What has been the biggest takeaway?

The biggest takeaway from this conference for me has been the solidarity. Most of us journalists think we are pretty isolated in our countries. Nobody was publishing me, but I guess in a global conference like this, you believe you are not the only one and there are many more who are parallel to you. We are all in this same battle together. A journalist from Nepal or Philippines has the same sentiment as me. They are all being censored by the political parties of the day. So you know that you are not in it alone.

What, in your view, is the importance of journalistic collaborations?

Publishing the story is definitely a bigger challenge than getting the story done. I went to every possible international news publication and none of them were willing to go against [India’s prime minister] Narendra Modi because they all knew he was going to be the prime minister of an important country. It is important that journalists can make contacts with other reporters in different countries who can help publish their stories. The collaboration should not be just over the ideation part.

Gujarat Files became a big name after I went to Al-Jazeera and [British journalist] Mehdi Hassan did a show with me. That’s when the book became an international name. Hassan reached out to me because he didn’t find any reports in the Indian media about my book. There were reviews of my book, but not a single report. I told him, ‘You give me a platform, as the media in your country is viewed by 65 nations.’ So that’s where collaboration works.

What is your biggest concern about investigative journalism in India?

My biggest concern is that these days in India, if somebody is given a hand-out from the Information Bureau, it’s called investigative journalism. I have a major problem with that. Investigative journalism is when you dig the heart and life out of a story. If you got the Panama Papers story, I want to know how you followed up on those people. More than just publishing names, following up on those names is a big deal for me. If information is being given out to you on a platter, that’s not investigative journalism. That can perhaps be called having good sources and a network, but that’s not investigative journalism.

Surbhi Kaul is a Delhi-based journalist who is involved with the Centre for Investigative Journalism, India’s first organisation dedicated to supporting and strengthening in-depth and watchdog journalism.

Surbhi Kaul is a Delhi-based journalist who is involved with the Centre for Investigative Journalism, India’s first organisation dedicated to supporting and strengthening in-depth and watchdog journalism.