Internet research specialist Paul Myers of the BBC shares tools and tricks for online sleuthing. Photo by Aseem Banstola.

Email addresses, Instagram photos of pizza, and websites selling handbags may seem innocuous but they can provide muckrakers with invaluable information.

In a fully-packed session at the Uncovering Asia 2016 conference in Nepal Saturday, BBC’s Internet research specialist Paul Myers demonstrated exactly how journalists can use tools and information available online to investigate subjects and sources. And how to avoid being discovered.

“What is a grotesque privacy invasion for you is also an opportunity to investigate other people,” he said, adding that journalists should protect their own data online.

Myers shared top tools and methods in uncovering deception:

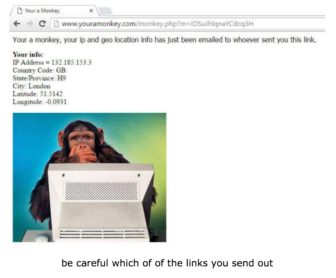

When tracking IP addresses, journalists should be careful which link they send out. Sites like youramonkey.com can give away their investigation. A screenshot from Myers’ presentation.

Investigate Locations

Myers said websites like whatstheirip.com allow journalists to get an Internet user’s IP address, and verify claims about where a person is.

“IP addresses are like the cellphone numbers of the Internet. Every site has an address. It can trace you back to your country, town and even place of work. Our Internet use traces us back to the BBC so we have to be careful about doing undercover work,” he said.

In a process that Myers calls “a crude honey trap,” a journalist can generate a link on whatstheirip.com to send to the person they are investigating. If the recipient clicks on the link, the reporter will get an email with the IP address and location.

Another website, www.hlr-lookups.com, traces a caller’s current active cellular network by mobile number, which can narrow down their location in the world.

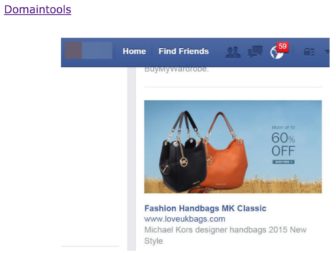

A screenshot from Myers’ presentation

Investigate Websites

There are also tricks to investigate companies’ domain names like www.domaintools.com.

Myers said his mother came across a website www.loveukbags.com that sold bags at prices much lower than in stores, making her suspicious.

“I did a domain search and I found out that [the company] is registered to an address in China. So it’s not a [British] company as we thought. The site also told me about other related websites selling handbags in Australia, France and Norway,” he said.

Journalists can also uncover hidden parts of a website by using pentest-tools.com.

Investigate Photos

Want to know where a photo was taken? Myers demonstrated how www.regex.info can identify where his Twitter profile pic was shot. The site reads metadata, or hidden information, in the photograph.

“It tells you what camera took it, the lens, the exposure, when the photo was taken, and that it was taken outside the BBC. Where somebody is when they take a photograph could be useful information. But they have to have geographic information (settings) turned on,” he said.

For mobile phones, photos can even include data on the time the photo was taken.

The website geofeedia.com can point journalists to social media posts published in a certain place, and the most popular words and users there.

“You might think Instagram is useless for investigations, just people posting pizza. But what’s important is where they are,” Myers said.

Investigate Tweets

Third-party Twitter tools help journalists find old tweets and draw connections between users.

All My Tweets lists every tweet a person posted, including from years back. The list can be saved and is easily searchable, Myers said.

Tweepsect.com shows a user’s followers.

“You can see who is following jihadists, other significant jihadists, but the most interesting are the mutual follows. This is really convenient for finding people with a shared interest in each other, perhaps colleagues working for one company,” he said.

Investigate Degrees

Platforms like LinkedIn are useful to check if someone is lying about academic qualifications. Myers said fake degrees are easily bought online, and journalists can check whether the university exists.

“People can buy bullshit degrees on the Internet called a life experience degree. You can buy a master’s degree, a doctorate degree, and have the documents sent by post, any degree, [with] free shipping too,” he said.

Citing Almeda University as the most famous bogus school, Myers did a LinkedIn search and found users working for organizations like the United Nations listing degrees from Almeda.

A word of warning from Myers: log out when using LinkedIn or use a Premium account so the user does not get wind of the investigation.

‘Jigsaw Identification’

No matter what tool journalists use, Myers said a method he called “jigsaw identification” will allow journalists to piece information together.

“By adding things, putting together small details you find, you can build a large picture,” Myers said.

“You have to look at it like a detective: follow different leads, find what’s unique to a person, what things they might like, where they live.”

For more tools and links, check out Myers’ website here.

Ayee Macaraig is a Manila-based journalist covering politics and international affairs. She is a correspondent for the French news agency Agence France-Presse (AFP).

Ayee reported on this event as part of the IACC Young Journalists Initiative, a network reporting on corruption around the globe.