AP journalists Martha Mendoza and Esther Htusan worked on ‘Seafood From Slaves,’ an international investigation that won the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service. Photo by Aseem Banstola.

Linking stories of slavery to big global brands forces change and moves readers and decision-makers to action, two celebrated Associated Press reporters told a room-full of investigative journalists at the Uncovering Asia 2016 conference in Nepal Saturday.

Martha Mendoza and Esther Htusan, half of the all-women AP team that won this year’s Pulitzer Prize for Public Service, exposed the practice of slavery in Southeast Asia’s fishing industry, which led to the liberation of more than 2,000 slaves, arrests of human traffickers, ship seizures, and new regulations in the United States. The team traced seafood caught by slaves to American supermarkets.

“You do these human rights stories, here’s this poor person [and] nobody in the U.S. cares particularly. But [since the story] if they’re in Wal-Mart, they’re like, ‘Oh, this is from Indonesia.’ That starts to have a real impact,” Mendoza said.

The AP reporters shared key techniques from their year-long investigation with journalists who also want to expose human trafficking.

Find the Victims

The AP team was frustrated with how little impact reported human trafficking stories had on the public, Mendoza said.

“We wanted to find somebody who was enslaved because every story was about somebody who was in a relief shelter telling people what happened but didn’t seem to be hitting it: capturing readers, change-makers. So let’s find somebody currently enslaved,” she said.

The journalists reached out to NGOs that worked on human trafficking as well as rescued slaves. Their stories led the team to the remote Indonesian island of Benjina, where they found mostly Burmese slaves in a cage begging them to tell families back home that they were still alive.

Htusan, a 28-year-old journalist from Myanmar, was called in to Benjina to help her AP colleague Robin McDowell, who was the first to arrive on the island.

“There was something about Benjina. I felt like it was the end of the world,” Htusan said. “These people were so shocked seeing women here. They said, ‘How come you are here?’ and they started telling us their stories.”

Esther Htusan, 28, is a member of Myanmar’s ethnic Kachin minority and the first woman from her country to win the Pulitzer Prize. She faced harassment and was chased by a speedboat while reporting the story. Photo by Aseem Banstola.

Follow the Supply Chain

The second part of the investigation was tracking the seafood the slaves caught, a painstaking process that involved noting down the names of boats in Benjina, following trucks in Thailand, and identifying supermarkets in the U.S.

With information from reporters in Benjina, Mendoza used marine traffic websites to follow the ship routes from the U.S. At one point she attended a seafood show in Boston, where organizers published her photo in a blog post, saying she was doing a story on labor abuse.

“We sweated to connect dots in the U.S. It took weeks and weeks of almost round-the-clock tracking. It was looking at hundreds of different companies, figuring out what brands they might make. We looked at a lot of supermarkets in the U.S. to look at the seafood,” Mendoza recalled.

The investigation found that slave-caught fish wound up in major U.S. stores like Wal-Mart, Kroger and Albertsons, prompting companies to review how they source their products.

Tap Technology, Help

To locate other slaves, Mendoza worked with government agencies and private companies that had resources she didn’t.

“We were frustrated knowing more [enslaved] men were out there. I called NASA, the [U.S.] Defense Department, and a number of other people to figure out who has satellite photos so we could identify the boats,” Mendoza said.

She finally found a U.S. company that had a massive satellite camera that tracked the boat she was looking for in an island near Papua New Guinea. “It’s like finding a moving needle in a haystack,” she recalled the company owners saying.

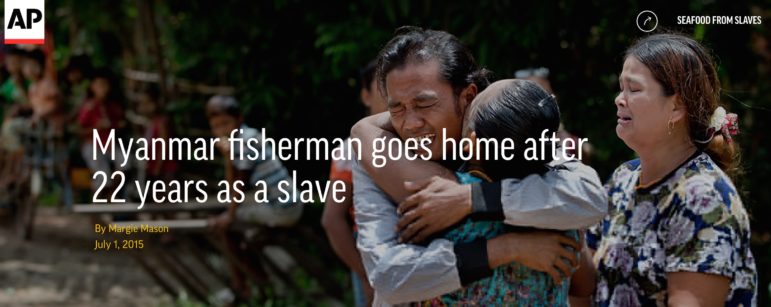

From AP story on the return of a freed slave to his village in Myanmar

Tell Impact Stories

The AP team told individual stories of slaves in Benjina, producing an interactive piece that showed their photos with quotes, including how they were deceived into slavery and beaten into submission with toxic stingray tails.

In a powerful narrative, Htusan followed a slave who returned to Myanmar after he was freed from Benjina.

“It was a heartbreaking reunion story. We felt we were part of this Hollywood movie. The whole village was crying. He was shocked to see his mother,” Htusan said.

The AP team also reported the information they uncovered to international organizations and Indonesian officials as they discovered additional slave boats.

“We had to make a decision where we would report the story [and] call the authorities and how to do both at the exact same time,” Mendoza said. “Many times we did both at the same time.”

Build on Previous Reporting

Asked how the team convinced their bosses to provide resources for an exhaustive investigation, Mendoza said her previous reporting on human trafficking helped her make the case. She had investigated child labor in the U.S. and those stories led to legislative changes. “We proved this could work,” Mendoza said.

“The most expensive cost was the trips to Benjina,” Mendoza said. “There was a telephone conversation with editors where we said: ‘We have good reason to believe people are trapped on the island. If we know where people are enslaved, we have a moral obligation to go.’”

The rest is journalism history.

Ayee Macaraig is a Manila-based journalist covering politics and international affairs. She reported on this event as part of the IACC Young Journalists Initiative, a network reporting on corruption around the globe.